In honesty, OIG didn’t come out and make that statement, but after reading a just-released report, missing the forest for the tress is exactly what seems to have happened. The Office of Inspector General (OIG) provides auditing services for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which oversees the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reports. In 2010, OIG reviewed CMS’s use of CERT data and reported that CMS and its contractors did not use this data to identify and focus on providers prone to having errors in their fee-for-service (FFS) claim submissions. CERT, or Comprehensive Error Rate Testing, is a program administered by CMS that calculates improper FFS payment rates that guide CMS’s education and remediation efforts.

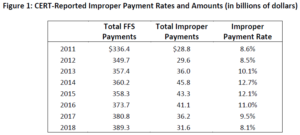

In 2017, OIG began an audit to determine if CMS was using the CERT data to identify and focus on what it called error-prone providers. (Remember that OIG first pointed out this issue in 2010.) In the most recent audit, which concluded in June 2020, OIG reviewed the steps CMS took to reduce improper payment rates for reporting years 2014 through 2017, the four highest years between 2011 and 2018. (See Figure 1 below from the OIG’s report.)

How does CMS’s CERT Program Work?

In a nutshell, CMS’s statistical contractor develops a statistical sample for the year’s CERT program activities which then pass to CMS’s medical review contractors. These individuals evaluate medical record documentation to determine whether claims were paid properly under Medicare’s coverage, coding and billing rules. The statistical contractor uses the medical review contractor’s determinations to estimate the rate of improper payments, called CERT data.

CMS monitors this information and launches initiatives, carried out by Medicare administrative contractors (MACs), such as pre-payment and post-payment claim review, education and TPE activities. Pre-payment reviews occur when the MAC makes a determination before the claim is paid, and post-payment reviews are done after the claim has been paid. When a claim is denied after post-payment review, the MAC provides details to the provider, explaining the error(s) in the original claim, in an effort to remediate faulty behavior.

Educational programs are multi-faceted: articles, webinars and meetings, coding instructions and coverage determinations focus on proper coding and processes to submit claims as well as coverage guidelines and the circumstances that support medical necessity for services.

TPE activities through the Targeted Probe & Educate (TPE) Program include one-on-one education to providers with high denial rates or unusual billing practices to assist in reducing claim errors and denials. Follow-up reviews are conducted to check on improvements or changes.

Back to the OIG’s Audit Findings

OIG identified 100 error prone providers who received $3.5 million in overpayments out of the $5.8 million reviewed by CERT, which represents a 60.7% error rate – much higher than the national average of 11.3% for all Medicare providers from 2014 through 2017. Although CMS provided contractors with a list of error-prone providers, it did not instruct the contractors on how to use the list. Moreover, the list did not include details needed by the contractors to readily determine which providers fell in their jurisdiction. CMS discontinued providing CERT data to contractors because it determined the CERT data was “ineffective” for this purpose.

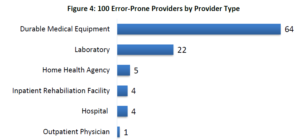

Instead, CMS focused its efforts to reduce improper payments on certain types of services, namely home health (HHA), inpatient rehabilitation (IRF) and skilled nursing (SNF), for which corrective actions would presumably have the biggest impact on the overall error rate. The OIG, however, drilled down on its list of the top-100 error prone providers and found that only nine fell in CMS’s focus area. Figure 4, below, from the OIG report, shows the composition of providers in the top-100 list. Keep in mind that CMS targeted home health, inpatient rehabilitation and skilled nursing facilities for remediation efforts.

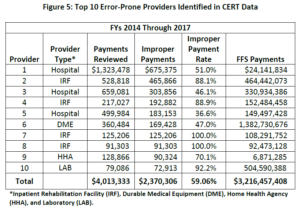

OIG then reviewed the top 10 error-prone providers by dollar amount and determined that their overpayments totaled $2.4 million, 60% of the $4.0 million reviewed by CERT. See Figure 5 below from the OIG report.

The OIG report summarized information for one provider whose error rate was 92% on a sample of 3,000 claims, and stated that errors were consistently high for each of the four years reviewed. OIG concluded that the magnitude and consistency of errors, along with the number of claims reviewed in the sample, provide “substantial evidence” that a large majority of the $500 million in FFS payments made to this provider between 2014 and 2017 were improper. And finally, OIG conducted simulation testing to confirm that the providers it identified were statistically more likely to submit improper claims than the average provider.

It would appear that, as OIG recommended in 2010 and in 2021, CERT data is somewhat useful in identifying providers who merit additional scrutiny. CMS disagreed, citing issues with the methodology used by the OIG and its conclusions. In the volley of comments between the two entities, OIG stressed that it was not suggesting CMS use CERT data exclusively or to discontinue using other tools that have proven beneficial in recouping improper payments. OIG was instead recommending that CMS add CERT data to its arsenal and give the appropriate value to the government’s investment in the CERT program, which has yielded important information that may preserve the Medicare Trust Funds.